These are the words of Amrita Sher-Gill, the artist who asserted her independence in the male world by carving a central position in Indian modernism. Refusing to let her emotional life compromise her art, which is normally admired in the male artist’s world, her profession always took precedence. Rashid Ahmad, one of her close friends, explains that, unlike other women of this time, she wasn’t overburdened by social taboos, and it was balanced by her self-discipline, which made her compose paintings in such numbers. Art was a question of life and death for her, and she never faltered in her faith of being a ‘genius.’ Despite a difference of a century, we don’t see a woman living on her terms but is still as brilliant as her in her profession. A free spirit, whose life rules were bent according to her choices and who placed herself beyond the norms of ordinary behavior, Amrita Sher-Gil was indeed the modern professional woman who was much ahead of her time. Though previously I wrote an article on her life, it is never enough to describe her art in a single read. Hence, today, in this article, I am introducing you to one of her favorite pictures she painted, Bride’s Toilet.

One of the lesser-known stories from her life is that she was so ferociously committed to her art that she would often offer ruthless criticisms to student’s work to toughen them up. For instance, when she saw the exhibition of Tagore at the Pigalle in Paris in 1930, she disagreed with Khandalavala’s comparison of Tagore with Soutine. She then further added,

“As for Tagore’s piddling little poetry, I have a profound contempt… the only thing that Tagore can do is paint.”

In 1937, she thought well of a Jamini Roy portrait at the Travancore Art Gallery. Partha Mitter in his book explains,

“Her most devastating criticisms were reserved for the Bengal School because even in decline its historicism defined artistic nationalism, which she needed to demolish in order to establish her own artistic authenticity…. She declared the renaissance in Indian painting led by the Bengal School was responsible for the stagnation of Indian art.” What she wanted to see is the art of India, “produce something vital connected with the soil, yet essentially Indian.”

Similarly, in 1937, she thought well of a Jamini Roy portrait at the Travancore Art Gallery and gave her detailed criticism of the paintings. However, these opinions were not limited to painting extraordinary compositions. Partha Mitter explains,

“Her most devastating criticisms were reserved for the Bengal School because even in decline its historicism defined artistic nationalism, which she needed to demolish in order to establish her own artistic authenticity…. She declared the renaissance in Indian painting led by the Bengal School was responsible for the stagnation of Indian art.” What she wanted to see is the art of India, “produce something vital connected with the soil, yet essentially Indian.”

To keep up with this thought, her paintings underwent a change in their theme, spirit, and technical expression. She composed the poor lives of the Indians during the British rule and “those silent images of infinite submissions and patience, to depict their angular brown bodies, strangely beautiful in their ugliness; to reproduce on canvas the impression their eyes created on her.” This was because she wanted her art to be Indian, a thought little to no artists have and this was one of the points that describes the story of her choice of subject for her later artworks, including the Bride’s Toilet.

The painting, Bride’s Toilet was composed during the last few years before the unfortunate death of the artist. In this action-filled seven years of 1934-41, Amrita had a vigorous painting career. From meeting prominent Indians to making trips to the ancient monuments and Ajanta, Amrita’s life was taking turns. After her visit to Ajanta especially, she started a new phase of work in Shimla. Starting with the painting, Girl With Pitcher, Amrita showed two dark figures in burnt earth colors against a liminal white background. To Karl, she wrote,

“In spite of the girl’s flaming red skirt, acid green bodice, and the yellow flowers in her hair, the figures are almost silhouetted against the background, an effect I have long been trying to achieve- without much success till now.”

This effect was well displayed in her paintings, The Bride’s Toilet and Brahmacharis, two of the most important works of Amrita Sher-Gil from 1937. While her career took a peek, her personal life was also significantly changing. Like, she married her doctor cousin, Victor Egan in 1938, a year after she painted this artwork.

Amrita always aspired to capture the romantic vision of rural India that was not captured before by any woman artist. Her later artworks included a

“Hungarian version of neo-impressionism, a post-impressionist ‘flat’ style reminiscent of Gauguin, the powerful influence of the ancient Buddhist paintings of the Ajanta and the final colorism.”

Hence, The Bride’s Toilet has the rural elements of India along with the powerful blend of the Hungarian influence in her Indian oeuvre and her Paris training. Due to these influences, Amrita touched on one of the most significant elements of the art that was rare for Indian art- the psychological depth of the portraiture of India.

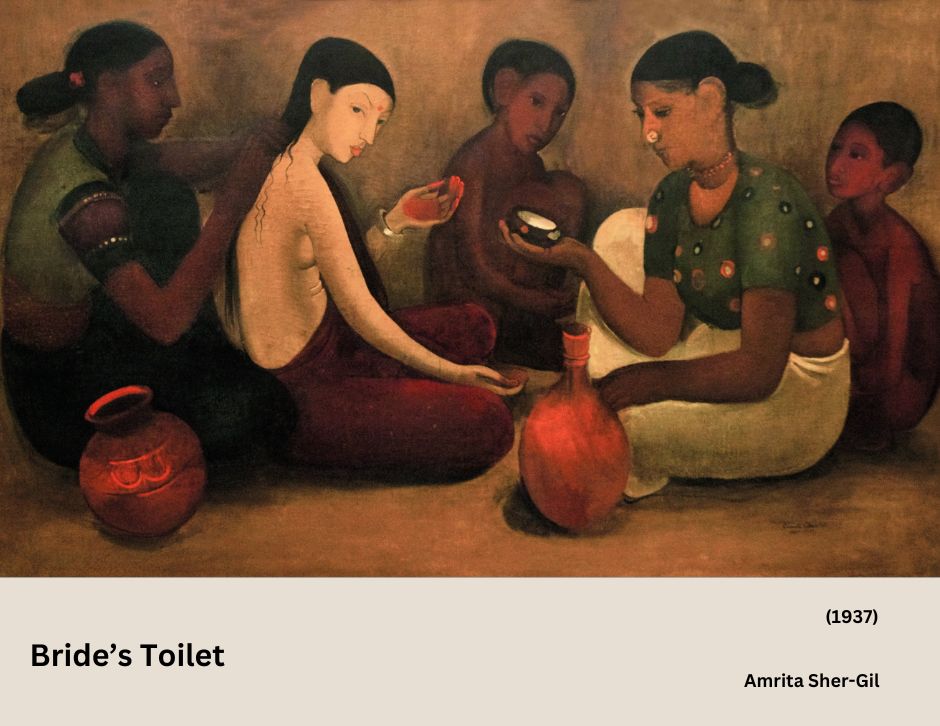

The Bride’s Toilet consists of a ‘flat’ style reminiscent of the Gauguin with the use of the austere shades of the Ajanta caves, developing her ‘formalist style.’ The frescoes of the Ajanta consist of a three-quarter face to convey the recession and dark skin color of the figures, which is why Amrita chose to paint with such a style. Further, she added austere shades such as red ochre to pick out the brightly colored figures and objects that we see in this artwork.

Portraying a scene of personal bathing, when a newly bride is taken care of by a better beauty regime like mud bathing, this scene shows the bride in red ochres with bright skin compared to the lady helpers and other figures of the artwork. Further, the painting shows the woman with fair skin having her hair braided and henna applied to her palms. The use of desolate figures of adolescent age, dark-bodied and sad faces of the helpers with incredibly thin figures is the indefinable melancholy regime in this artwork. To showcase simplicity, Amrita used a local color palette here. The deep burnt red colors of the earth and the insensate whites might be because of Amrita’s enthusiasm for color after Van Gogh compounded with Ajanta’s trip. Looking at the subject closely, the bride in this painting looks melancholic as she gets dressed by maids, and two children observe her, a theme which is often repeated in the Indian miniatures. The theme is not eroticized, but the grave atmosphere is enhanced and romanticized by the sombre red hues and browns, further creating a reflective ambiance. Amrita writes by herself to describe the color scheme of the painting,

“I wanted to send you reproductions of my two latest masterpieces but due to the usual punctuality of Indian photographers this is only possible now, hence the delay. Since the group of women was photographed I have worked a good deal on it. Having a picture photographed is, I find, an excellent way of finding out its defects. J’ai serve les formes d’avantage. I have defined and made more compact the best of the fat woman on the right and have also defined the upper portion of the woman’s body on the right and have also defined the upper portion of the woman’s body on the extreme left, worked on the hands and feet of the child on the extreme right, and in short greatly improved the whole picture. The fat woman’s skirt is unexpected greenish yellow, lights up the whole picture. The little girl in the middle is clothed in crimson cloth with white circles, her face and body are a sort of ivory color. The woman doing her hair is a rich burnt sienna with reddish oranges in it, her skirt is a warm peacock blue, her blouse acid green with purple sleeves, the pots pink, the whole background and foreground a greyish ochre more or less uniform in color which the photo does not show (rather varied in brush work though). The kid in the center is a deep red-brown with occasional green tinges and the child on the extreme right is as though lit up by a flame, as somebody said. The fat woman’s face and body are yellowish ochre.”

Conclusion.

Being one of the most significant painters of melancholic rural India, Amrita’s Bride’s Toilet was close to her heart as she finally thought that her art had a language that communicates, as she says, “best thing so far.” And I feel no matter what she portrayed, whether melancholy or cheerful India, it is her abstract idiom with the distancing effect in her elegiac paintings of the villagers that speaks more to the visitors. Though immersed in daily activities, she shows the impassiveness of the figures to give an impression of the state of equilibrium and immobility. And we finally understand the woman’s perspective of the old society, a rare aspect.

Resources.

- The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-Garde by Partha Mitter.

- Featured Image: Bride’s Toilet by Amrita Sher-Gil; Amrita Sher-Gil, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India by Geeta Kapur.

- Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life by Dalmia Yashodhara.