For Klimt, women were amusing, probably a muse shrouded in mystery, which we can see clearly in Judith I. But most importantly, they were covered in Gold, as if they were the supreme creatures, mounted on the precious surfaces like jewels and icons of a new religion. While this reverence for women carries complexities and potential pitfalls with it, the 1901 painting Judith I stands as a testament to female empowerment and allure. Through this work, he not only celebrates the femme fatale of his era but also boldly inaugurates his signature golden style, reflecting both artistic innovation and a profound appreciation for his subjects. Being the son of a goldsmith, Klimt used gold over his canvases in remembrance of the shining memory of his childhood, as well as to depict the women with the timeless material of regal seduction. But the most important reason behind the use of gold was that he discovered its use as a decorative function in the painting Modern Amoretti (1868) by Hans Makart. This made the artist experiment. However, it’s not all about the massive use of pure gold leaf and gilded paper; Klimt added a massive structural role to the figures of his canvas. Hence, this article is about the first painting from the artist’s gallery, Judith I, which exhibited his signature golden style, and an explanation of the structural role of the figure.

Judith I | Fast Knowledge

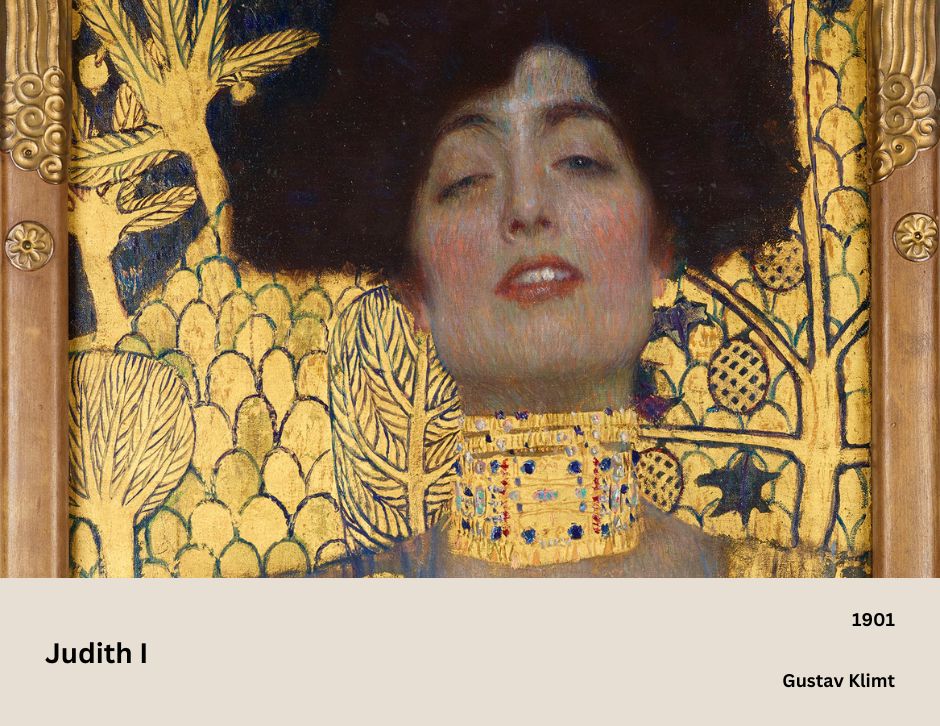

Judith I by Gustav Klimt is a 1901 oil-on-canvas painting inspired by the apocryphal Biblical story of the Jewish heroine saving her people by cutting off the head of Holofernes. The artwork shows an obvious modernity and air of sensual gratification, suggesting women’s sexuality as a destructive force.

About the Subject.

The painting, Judith I, portrays a female archetype in a seductive and deadly manner through her naked torso. Having a rosy body as if a bouquet of roses is boxed among jewels, this female governs the decadent fantasies of an era with the imagination of the artist. In fact, this image is not a conventional picture from history, like the depiction of Pandora, Lilith, Medusa, Circe, Helen, or Astarte, but a portrayal of the new age female who is very much involved in the age of industry and great cities. Hence, the illustration of Judith has an ancient fantasy and a modern idea, making her power of feminine seduction further outflank the positivist pride. However, at the same time, gold imprisons the bejeweled phantasm of the era’s misogyny, suggesting the return of the remote and inescapable memory. I will explain about the possible interpretations of gold usage in the later sections of the article.

A golden frame with the large letters, written “Judith and Holofernes,” the picture portrays a background of gold trees with the vegetable ornamentation in the lower half. Standing against the background, a half length portrait of the female wearing a wide gold collar alongside a gold girdle covering her hips is shown. You can see the partially clad model with a cloth falling over her right shoulder, covering her breast. She looks at us with a squint having her lips parted. At the same time, she holds the severed head of Holofernes.

It is significant to note that the man-murdering woman is not shown here as devious; instead, she is shown at the moment of his death or shortly after it, possibly with a sword in her left hand, knowing the picture is a cropped style portrait. Only the half-recognisable severed head of Holofernes is visible here. Klimt portrayed Judith not as the war-like heroine but as a sensuous and lascivious woman. In 1903, Klimt’s contemporaries suggested an interpretation of his depiction of Judith. Felix Salten wrote,

“This Judith… is a lovely lewish lady of the day… who turned all men’s heads towards her at every premiere. A slender, sinuous creature with smouldering fire in her dark eyes and a cruel mouth… puzzles and powers seem to slumber in this alluring woman, energy and violence impossible to curb if the glowing coals are dampened by bourgeois society were ever to ignite. An artist has stroked the fashionable clothes from their bodies, taken one of them and presented her to us adorned with her timeless nudity…”

The painting consists of the contrast between the naturalism of the face and the gesture, with an absence of depth on the radiant decorative plane. The face of the subject is slightly leaned back as if in a small trance; she has a wandering smile with her languid eye barely closed and mouth half-open. While she desperately shows a sensuous expression with a devilish thought behind her because of the power she has, she lightly holds the head of Holofernes, her victim. The heavy collar of the gold and precious stones chains her to the background, further visually separating her head from her torso to reintroduce the decapitation that drives her oblivious pleasure. The frontal pose of the figure with a cutoff at the height of the pelvis further puts an accent on the navel of Judith, which we also saw in Munch’s picture Madonna (1893-94).

The most amusing thing about the picture is that the painting consists of an ancient fantasy mixed with a modern idea, as I said earlier. The background of the painting consists of trees, mountains, and vines, which are reproduced on the Assyrian relief from Sennacherib’s Palace in Nineveh, an archaeological quote to indicate the distant past of the artist. Further, the use of gold invokes the original depth of the earth as if the light is preserved in the womb. The Modern Idea here is the look of Judith that is shown through the face with silky skin and nearly photographic illusionism. Several of the contemporaries believe that the Viennese lady of the epoch might be the model of the Judith I painting.

Judith is sensual as if she is inaccessible as an idol, but she is delicate like a flower with living flesh. There is a longing, nostalgia, and a fear that shape the male erotic imagination of the time. Further, she has a feminine erotic self-sufficiency as if it escapes all comprehension as well as all possession. The critic Hevesi defined this composition as,

“Concentrated poison like that which was once set inside previous antiquities.”

Of course, Judith is sensuous, but more than that, she is evil. She has an evil orgasm, but what makes it evil is her hideous condition under which it is achieved- the death of her partner. This coupling of death and sexuality is worth noticing in the painting, as it fascinated Klimt and even Freud and several other European audiences.

The unequivocal Judith and Holofernes frame is separated from the content as Klimt picked the idea from the Bible, which is easily seen through its subject and with an archaeological slyness unremarked by the contemporary viewers, a specific Biblical site that has reference right into this picture. The composition consists of a potent sensualism, further transferring the sinful lust of Holofernes into the femme fatale eroticism. There might be a possibility that he might not have presented Judith as a Salome, but one of the things that was certain was that he particularly showed her as a personal slayer of lust, and a more spellbinding representative of Eros.

A Closer Look at Judith I.

The painting depicts Adele Bloch-Bauer, who looks at the viewer directly with the promise of erotic delights as if she were to let the mask slip and cast aside the glittering armour. There is a sense of passion in the subject, waiting to just explode, as if a wild female is caged in by the social conventions. However, that is not all. Klimt depicted her as an example of the vamp, familiar in the literature as well as the art of the period, who is irresistibly seductive yet deadly to the male. She appeared in Klimt’s work in several disguises, but here he displayed her in a personification of seduction and threat to the man. But there is an expression of a predatory female in the subject as it reflects the artist’s feelings on women at a deep and subconscious level. Most of the time, he showed Judith essentially as a sexual being, implying to the male viewers that the subject enjoys their bodies and sometimes even pleasure themselves.

| Painting | Judith and Holofernes, Judith I |

| Artist | Gustav Klimt |

| Year | 1901 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 84 x 42 cm |

| Museum | Osterreichische Galerie, Vienna |

Klimt painted Judith again in 1909 and there’s a significant difference between Judith I and Judith II. The 1909 version of Judith is manneristic with extreme decoration. In the 1909 version, gold is found only in light spiral decoration at the bottom with a colored puzzle of cloth and ornaments. There is a disturbing expression in Judith II, further lacking the sweetness of the voluptuousness that suffused the first Judith. Further, it doesn’t hold a direct relationship with the viewer that Judith I had, as she is captured in her own tapestry. While Judith I is only about a theme of eroticism in the femme fatale, Judith II revolves around the theme of devouring women.

Did You Know?

Klimt had a charming sexuality with his subjects being the talk of the town in Vienna. Though he was discreet in his relationships and there is very little information on whether Klimt had relations with women, the topic was well known to several people. One of the women whom he pursued very much was Alma Schindler, the daughter of a painter, and the future wife of the composer Gustav Mahler, the architect Walter Gropius, and also of the writer Franz Werfel, and mistress of the painter Oskar Kokoschka. When she recalled her teenage years in her autobiography, she remembered that Klimt actually was interested in her at that time. Although her mother firmly disapproved of the fact, Klimt repeatedly visited her at home and even followed her on her travels. She wrote,

“Wherever we were, he would appear. So we came to Genoa, my family and Klimt, who was following me. Here, the course of our love was disturbed by my mother in a horrible way. Breaking her promise, she read what I wrote in my diary every day and so knew about the stages of my loving relationship. And- oh horrors!- she had to read that Klimt had kissed me… With Gustav Klimt, the first great love came into my life, but I was an innocent child.”

A Little History of Judith I.

First things first, let me tell you who Judith was. If you have read my article on Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi, you might remember the story of the Biblical heroine. However, I will still bring some light to her through this section. Judith is not the Old Testament heroine who used her wiles to kill and decapitate the man who murdered her husband; as Salten explained,

“A beautiful Jewish salon hostess of the kind one sees everywhere, attracting the glances of the men as she arrives at a premiere, her silk petticoats rustling. A slim, lithe, and supple woman with a sultry fire in her dark eyes, with a cruel mouth and nostrils trembling with passion. Mysterious forces appear to slumber in this seductive female, energies and a violence which, for the moment, are forced to glow only with a bourgeois dimness, but which, once ignited. could not be put out.”

Coming to the historical provenance of the composition, Klimt painted the first Judith in 1901. But by this time, he did not want to depict her for the noble cause or for being the Biblical heroine; instead, he wanted to display something closer to what the female decapitator exercised on Sacher-Masoch. But before Klimt painted his Judith, Franz von Stuck and Carl Strathmann painted their Judiths in the triumphal contemplation of the man’s severed head. The most important question is, why did Klimt choose the name Judith to display an assassin? It’s because the artist clearly wanted to celebrate a grown woman whose presence caused the king to abdicate his power and concede. Judith is herself a power who would never ask but decide and who would use her own hands to actually commit a crime, making her the queen of her own desire.

The Pallas Athene of 1898 has been the rational artwork of the artist and just three years after the composition, Klimt painted Judith I, which stunned and enthralled the Viennese critics with its terrifying invocation of the irrational. Though Klimt took the character of a Jewish widow and courageous heroine, he depicted her as dreadful, due to which many of the critics first thought that the painting depicts “Salome.” But what Klimt was interested in was carrying over from Salome precedents, such as the Klinger marble statue of 1893. Klimt’s Judith I certainly was an answer to depict the femme fatale of Sin. But most importantly, Klimt portrayed the phenomenon of mutilation on three levels: the decapitated head of Holofernes, the jeweled-collar cleaving of Judith’s head from her body, and finally the compositional bisecting of Judith’s torso by drapery placement. Further, the torso amputation, which Klimt used here, was adopted in toto by Schiele for his tortured self-portraits and pictures of thrashing female bodies.

Symbolism Behind Judith I.

Klimt explained and expressed his admiration for female beauty in several of his paintings. But while expressing his admiration for women’s beauty, he articulated her remoteness and a bridgeable distance between man and woman. Hence, he painted women as an eternally mysterious creature who is unapproachable by man. It’s like he showed the lustful beauty of a woman, but the sin is by the man’s side. In this composition, Judith is shown as a woman who not only conquered men with her lustful beauty or her own weapons, but her peculiar sense of power and logic. He painted women as a witch and as a sorceress, as if they were meant to destroy men.

Final Words.

The painting doesn’t show the usual message of the liberation of Judith’s native city from the Assyrian besiege. Instead, she is shown as a woman who turns into a seductress, a man-threatening sexual state. The figure had a powerful characteristic in her, as there is a challenging gaze and nudity, with the breasts exposed to view. Judith is sensuous and beautiful with a pride in her body. And, this pride is immediately visible through her gaze. Even when she holds the head of Holofernes, there is an easy grip, not necessarily to show her anger or anguish over him. The structural core of Judith I is not just a lustful beauty but possibly the sinful impact of lust.

Resources.

- Featured Image: Judith I by Gustav Klimt; Gustav Klimt, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Gustav Klimt by Gilles Neret, 1862-1918.

- Gustav Klimt: Art Nouveau Visionary by Eva Di Stefano.

- The Life and Works of Gustav Klimt by Nathaniel Harris.

- Gustav Klimt by Frank Whitford.

- Women by Gustav Klimt, 1862-1918, Angelica Blaumer.

- Gustav Klimt by Jane Rogoyska and Patrick Bade.

- Gustav Klimt (Life and Work).